The Achievement Gap

by Kayla Gonzalez

School is a place of growth, exploration, and opportunity, where youth establish important connections that provide guidance, encouragement, and a strong foundation for their future. Yet, every student comes from a different background with different abilities, skills, and needs in the classroom.

For many diverse and often disadvantaged groups, such as English-language learners, racial and ethnic minorities, disabled learners, and students with low-socioeconomic status, learning differences have historically been understood through assessment data and met (at least somewhat) by targeted instruction. But recent data has highlighted the achievement gap between students in foster care and their peers, showing that foster youth are missing the resources and adequate support to ensure that they will thrive academically.

Until recently, California public schools had few resources to gather and analyze data on their students who were also foster youth. Administrators were unable to identify which of their students were in foster care or track their academic performance. The inability of educators to determine where foster youth fall behind has impeded their ability to meet the needs of students. Without the extensive educational services that are provided for other learners, this acts a major barrier to success.

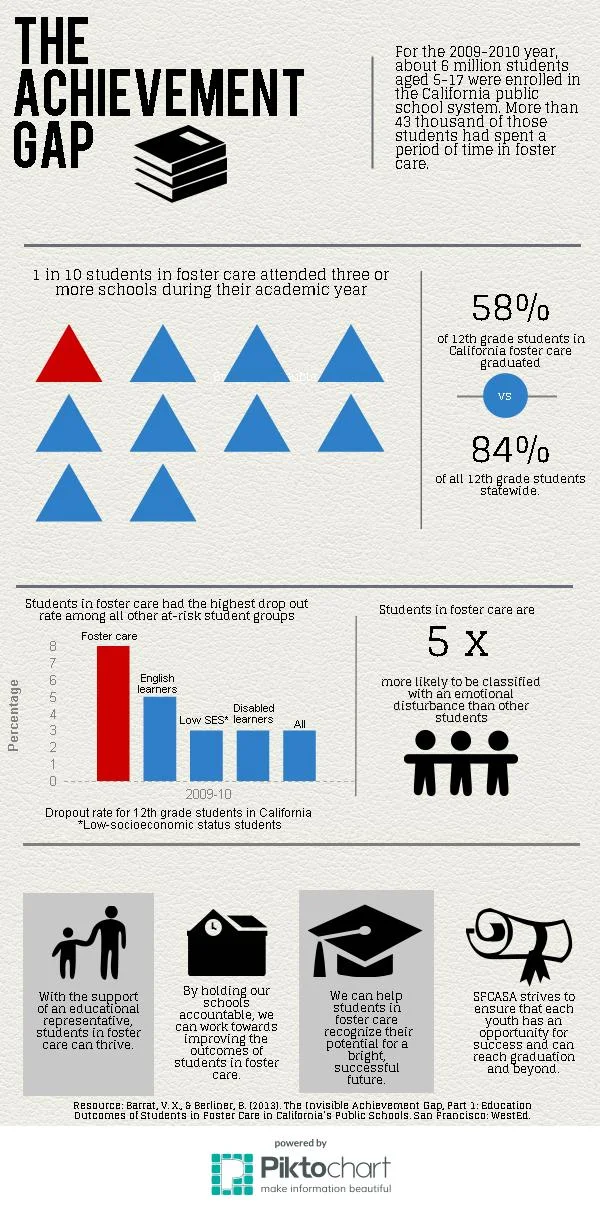

The Stuart Foundation’s study of the Invisible Achievement Gap gathered statistics on the 2009-2010 California public school year, where they found that foster youth are trailing behind their peers far more than educators thought. Of nearly six million K-12 students enrolled in California’s public school system, one in every 150 had spent time in the foster care system during 2009-2010. The report's findings also revealed that students in foster care were generally older for their middle and high school grade levels, and that they were twice more likely to have a disability than the statewide population.

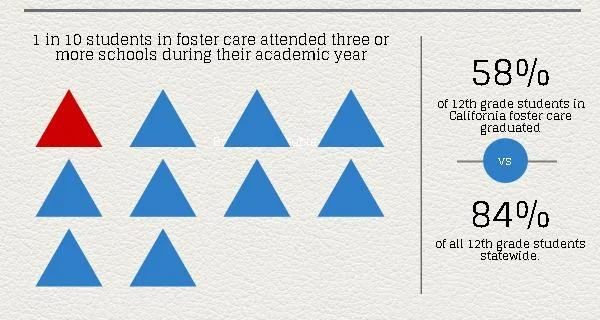

With the highest rate of any other learning group, students in foster care were five times more likely than those with an established disability to be classified with an emotional disturbance. At 8%, high school students in foster care had the highest single-year dropout rate than any other group; about three times higher than the dropout rate statewide. The graduation rate for foster youth in 12th grade was only 58%, compared to 84% for 12th grade students statewide.

Additionally, the poor academic performance of a youth, behavioral challenges she may face, or frequent housing rearrangements could lead the youth to be transferred to a new school. For 2009-2010, 7% of students in foster care attended three or more schools within the school year, compared to 1% of all students statewide. On average, California’s foster youth attend seven to nine different schools by the age of 18. Lack of permanency can mean a student in foster care loses months of progress with each school transfer, also losing the familiarity of classmates and teachers.

The California public school system has a responsibility to ensure each foster youth has a viable opportunity for academic success. The findings from the Stuart Foundation have caused a push to put a Local Control Funding Formula into place, a shift in California’s school finance model that moves much of the decision-making from state control to local control. This law provided the 2013-2014 school year with funding that holds California’s schools, districts, and counties responsible for identifying students within the foster care system and tracking their performance for the years to come. By holding districts and schools accountable, educators and administrators now have incentive to ensure the achievement goals of their students in foster care are met. Hopefully, this change will mean that students in foster care can now receive the same services as other disadvantaged learning groups to ensure their educational outcomes are drastically improved.

The Stuart Foundation study and the implementation of the Local Control Funding Formula continue to inspire more research and programs that will give students in foster care an opportunity to succeed academically. Although California has done a good job implementing new practices to improve the educational outcomes for students in foster care, educators and administrators must continue to provide academic, social, and extracurricular support to foster youth. Outside of the classroom, an educational representative, such as a CASA volunteer, can help a youth reach high school graduation or serve as an advocate who fights for additional educational programs. By asking ourselves what initiatives our schools and districts can take to help foster youth succeed, we begin to give them a fighting chance.

View the full infographic on the Invisible Achievement Gap below